Between the sixteenth and seventeenth century, the Church, influenced by the Council of Trent and the Protestant Reformation, redefined religious doctrine and practice, strengthening its ranks and rejecting all preaching contrary to its dogmas.

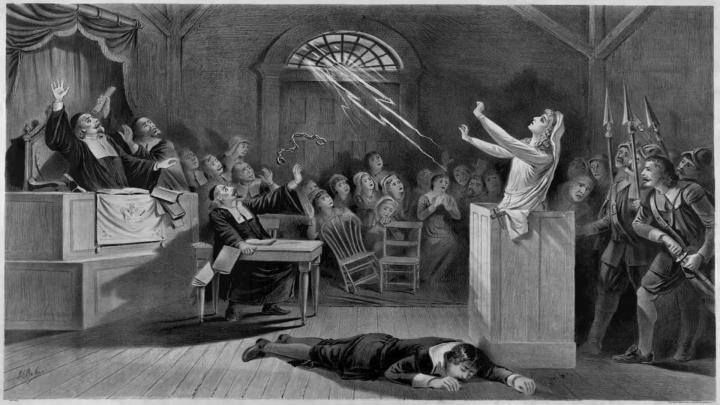

Magical practices, which had been tolerated during the Middle Ages, were also banned in Piedmont. Witchcraft was then equated with heresy, therefore considered a crime and prosecuted as such. Civil and religious courts, in a crescendo of intolerance and violence, intensified witch hunts.

The Church began to judge women as the origin of all vices. Like heretics and Jews, women, especially the poorest and least protected - orphans, old women, widows - also became the scapegoats for tensions originating elsewhere. In other words, if a woman, who was not noble and wealthy, manifested "eccentric" behaviour and was not submissive to men and dominant values, she became a threat to the social order. A woman could be accused of witchcraft on the basis of suspicions, hearsay, and flimsy evidence.

Confessions were generally extracted through torture, and the accused ended up admitting those ignominious faults. Many were the victims, unjustly sacrificed by the prejudice and injustice of the time: from Antonia of Zardino, to the witches of Suno.